What only very few of us know from the inside is the most obligatory gimmick level of all in video games: the prison. (Supposedly) deprived of freedom and often stripped of (almost) every item, not only Princess Peach asks herself: What now? Our Mixtake tries to get closer to the sense and nonsense of prisons that have become a game.

Should I stay or should I go?

The average number of prison breaks per year in Germany is somewhere below ten, with a downward trend. With just under 50,000 prisoners, the situation is clear: It’s in, not out. Prisons in videogames are the exact opposite, the imperative here is “get the hell out of here!” and it’s usually not even too hard to find the gap in the system and make off.

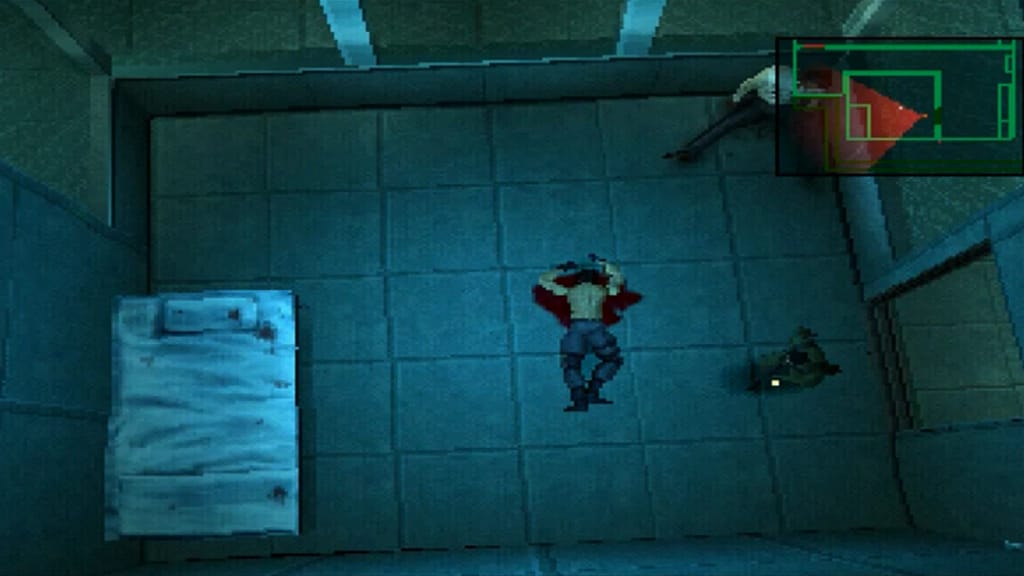

Some prisons, like the Duke’s Library (Dark Souls) or the basement vault in Yahar’gul (Bloodborne), don’t deserve the name: open the door and get out. Others need at least one skill – a clock with a magnetic function in Goldeneye 007 or a hole digging in Twilight Princess. Metal Gear Solid offers us several options to trick the diarrhea-ridden guard Johnny. But it’s always clear: we’ll get out, that’s the game’s intention. On the other hand, not wanting to escape from prison is tantamount to refusing to work.

(Scene from Metal Gear Solid)

We don’t ask ourselves the question of why we are in prison in the first place when we break out. Perhaps the answer scares us. Once we put aside the gameplay benefits of bars, we begin to suspect that we may have been imprisoned for a reason. How many henchmen, side characters, and troubled creatures could return home in the evening and tell of a day without any special incidents, laughing with their friends and playing with their children, if my character, who mostly only knows how to kill, would just stay in jail for a while? Is the virtual world really in such a mess if we were to refrain from slaughtering, shooting, rampaging, driving around for some time? These are enormously serious offenses for which we would rightfully go to jail in the real world. Well, at least the prison break itself, the assertion of one’s right to freedom, is not a crime.

Fall of Man

One must justify the existence of prisons well, because imprisonment is a massive encroachment on fundamental rights. It is also expensive and a long stay jeopardizes resocialization. And yet there are good reasons for locking people up. Most often, the emphasis is on a general sense of justice and deterrence. But there is at least a third function of imprisonment: prevention. A mass murderer is unlikely to continue killing in prison, and if he does, at least it will affect other mass murderers.

But as Mirko says in his text, it is all too easy to forget these good reasons when playing video games. There is no questioning whether one should escape. Even more: you are constantly encouraged to free strangers. It’s a natural instinct to open locked doors in games, and you’re usually rewarded for doing so. Unless there are zombies behind it. In that case, you can be sure that the doors will open by themselves at an inopportune moment.

The detective mystery adventure The Forgotten City uses this logic to its advantage. [SPOILER] Right at the beginning, you are greeted by Galerius. A simple farmer esteemed by all, he seems the perfect choice alongside the two shady candidates for the highest office. The current incumbent has imprisoned a severely mentally impaired man named Duli because he keeps trying to steal.The detective mystery adventure The Forgotten City uses this logic to its advantage. [SPOILER] Right at the beginning, you are greeted by Galerius. A simple farmer esteemed by all, he seems the perfect choice alongside the two shady candidates for the highest office. The current incumbent has imprisoned a severely mentally impaired man named Duli because he keeps trying to steal.

Now, you have to know that the basic premise of the game is that committing a sin like theft results in the divine execution of all inhabitants. To protect the community from Duli – and Duli from himself, he would have to go behind bars. Galerius finds this unjust, because Duli has no evil intentions, but the magistrate remains firm – it is not the intentions that count, but the deeds. And since, according to the magistrate, Duli will never be able to control himself, he will have to spend the rest of his life in the cell. All the positively drawn characters are against it, and Duli himself also pleads urgently to be released.

And even those who believe the magistrate and cold-heartedly ignore all signals suggesting release will end up with a stone tablet. The last of four stone tablets, which is absolutely necessary to end the game, is in Duli’s cell. So many things are set in motion to secure the election of Galerius and his first official act is indeed Duli’s pardon. The latter affirms that he will not steal anymore. The magistrate must really have been too harsh. But if you stand next to Duli’s cell, you can watch Duli walk out of the prison and straight towards the nearest market stall. Duli catches sight of a random object and takes it. Immediately, the golden guards:inside come alive and kill everyone. It’s a delightful punchline that builds throughout the game and reminds us that even in video games there can be reasons to use a prison, however inhumane it may seem.

Under construction

Fortunately, you don’t have to be sentenced to prison to get involved with prisons in real life or in video games. After all, “construction” comes from “building”, and because I enjoy this occupation, I spent many hours behind bars voluntarily in Prison Architect.

Between communal showers and electric chairs, as a warden I can fully concentrate on optimizing everything instead of mothering my inmates too much. While I naturally allow my beloved Sims a larger living room if I want to accommodate another pretty reading lamp, or spoil my Zoo Tycoon animals with a bit more space than necessary, strict pragmatism prevails in the prison. The minimum size is sufficient for any cell, don’t get in line! Could the Stanford Prison experiment be right? Do we automatically lose empathy in the role of the prison guard? But that’s not my point, so let’s quickly put the moral discussions aside and talk about game mechanics.

Part of my perfectionism in Prison Architect is that I plan my buildings very precisely. And there is one tool that I always wonder why I don’t have in EVERY building game: The planning mode. It allows you to draw in the shape of buildings directly on the map as an overlay, including doors and rough placeholders for objects. What a blessing! Finally I can try out without obligation how my symmetrically (of course they have to be symmetrical!) arranged rooms fit into the courtyard in such a way that there is equal space to the wall on all sides. No more exhausting counting of boxes in my head, where I always end up getting one wrong. No more tedious building and tearing down. How I would love to have this option in every game without exception where I have to plan buildings, cities or theme parks. But alas, it still doesn’t seem to have caught on to the degree I had hoped. And so, when I think back to my time with Prison Architect, I still think back with love to the planning mode I first discovered there. As coldly as I may have treated all my inmates during my time as a Dirketor, their tiny cells were wonderfully symmetrical.

Hard times for silent Ps

I was locked up because I had emphasized silent Ps now and then.

I received a sentence of sixty days. At first glance, this may sound exaggerated, but as a student of German studies, I can find a little bit of merit in the matter. The things that happened in prison from now on were more problematic:

First, an inmate wanted me to dress exactly like him. I didn’t feel like it, because said inmate was extremely badly dressed. He didn’t think much of my negative attitude and involved me in a fight. I survived this more badly than well, but was at least able to hold my own a little.

Shortly after, another inmate came up to me and asked me about my brawl. He invited me to join his gang because it was better to survive together. Now, I was only in jail for a Germanic offense and didn’t think it was a good idea to join any gangs. The gang follower left, but warned me that there would be consequences.

Out of sheer excitement, I forgot to go to the bathroom, so I peed on the floor of the library. Immediately, I was dragged to court by a guard. Fortunately, my judge was well-disposed towards me and did not extend my prison time. But the guard didn’t like me anymore.

After I left the courtroom again, I retroactively entered the prison toilets to implement any outstanding emptying. There I saw a syringe lying on the floor with a pink liquid in it. Of course, I injected myself with it immediately, since I had learned from superhero movies that this could actually only mean good things.

Unfortunately, a female guard saw me running around with the syringe in my hand, brought me before the judge again and this time he showed no understanding. My sentence was extended by five days. Damn.

Frustrated, I went to my cell in the evening to lie down, but was visited by the gang member from before. The guy didn’t come alone, but brought a shotgun. He shot me several times, I collapsed, but actually managed to stand up, fling myself against him, and wrest the gun from him. I fired a shot, but didn’t aim right, hitting the guard, who was still mad at me for the library urination, immediately pulled out a submachine gun and shot me over the head.

Now I am dead.

I survived two days out of sixty-five.

And that’s just because of that stupid, dumb Ps.

Hard Time is one of the best prison simulators out there.

This post is also available in:

![]() German

German